Let’s be honest—superstitions were probably one of the first “rules” you ever learned growing up in an Asian household. I mean, who else got scolded for whistling at night or dared to cut their nails after dark? If you’re anything like me, these quirky warnings weren’t just weird bedtime stories—they were gospel. And even if we didn’t totally believe them, we still kinda listened. Just in case.

But here’s the thing: those seemingly silly rules? They’re packed with meaning. For many Asian Americans, superstitions aren’t just superstition—they’re memory, culture, protection, and identity all tangled together.

Let’s dig in.

Superstitions Aren’t Random—They’re Cultural DNA

Growing up, my grandma had a whole list of things I could and couldn’t do. Don’t sweep at night (you’ll sweep away fortune). Don’t point at the moon (your ears will fall off). Always eat every grain of rice (or your future spouse will have acne). I remember rolling my eyes so hard at some of these. But years later, I caught myself telling my younger cousin not to leave chopsticks sticking upright in rice… and suddenly realized, oh no, I’ve become her.

That’s when it hit me—these beliefs were never just rules. They were little rituals passed down to keep us connected to a world we didn’t fully grow up in, but still belonged to.

Think of it this way: if your culture is a language, superstitions are like idioms. They’re weird, specific, and don’t always translate neatly, but they’re rich with emotion and tradition.

The Ones That Stick

Here are a few you’ve probably heard in some form or another:

Avoid the number four – In Mandarin and Cantonese, “four” sounds like “death.” It’s the reason so many apartment buildings in Asia skip the 4th floor.

No whistling at night – Because that supposedly invites spirits. I don’t even know which spirits, but trust me, I wasn’t trying to find out.

Eat all your rice – “If you waste food, your spouse will have pimples.” Okay, maybe that’s a bit of a stretch—but at its core, it teaches gratitude.

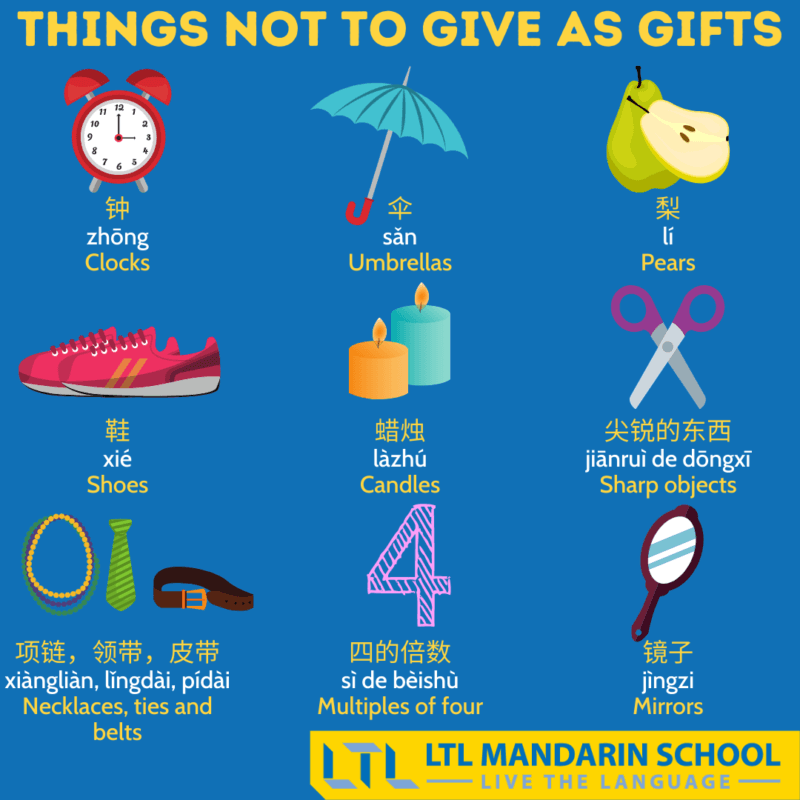

Don’t gift clocks – In Chinese culture, giving someone a clock is like counting down to their death. Super unlucky.

Sure, some of these feel outdated. But they’re also a lens through which love and care were shown, especially when words weren’t always easy to express.

When Superstition Meets Science

As we grow up surrounded by STEM classes and logic-based thinking, it’s natural to start questioning this stuff. I remember asking my mom, “Why can’t I cut my nails at night?” And she just said, “Because my mom told me not to.” That was it. End of story.

But even without “proof,” people still hold onto these beliefs. Why?

Dr. Yan Zhang, a psychologist who studies cross-cultural behavior, explains it beautifully: superstitions help us feel in control during uncertain times. For immigrant families, especially those navigating an unfamiliar country, superstitions offered comfort, structure, and even a bit of magic when everything else felt unpredictable.

Generational Clashes (aka the “But Why?” Phase)

Now, here’s where things get interesting—and maybe a little heated.

In a lot of Asian American households, superstitions can become a battleground between generations. Our parents or grandparents might hold on tightly to rituals, while we ask, “What’s the point?” And when we push back, it’s not always received as curiosity—it can feel like rejection.

One of my friends, Jenny, shared how her family insisted on burning paper money during Qingming Festival, even though she didn’t believe in the afterlife. But instead of arguing, she helped out, and asked her grandma to explain why it mattered. “It was less about ghosts,” she told me, “and more about showing love to those who came before us.”

That stuck with me.

Reclaiming and Reimagining

Younger generations are starting to put their own spin on these traditions. Some people follow the superstitions they resonate with, while letting go of the ones that feel harmful or outdated.

Take artist Peter Chan—he incorporates Chinese folk beliefs into his modern art to explore the tension between heritage and identity. Or friends who keep the “no chopsticks in rice” rule at the dinner table but ditch the “girls shouldn’t whistle” one.

It’s not about erasing the past—it’s about making it fit into our lives today.

Superstitions as Emotional Language

If you think about it, many of these beliefs were rooted in deeper values:

Respect for the dead (no whistling, no upside-down shoes, rituals for ancestors)

Gratitude and humility (don’t waste food, bow to elders)

Protection and love (no sharp gifts, avoiding bad luck numbers)

So while we may not fully “believe” in them, we can still feel them—and sometimes that matters more than facts.

A New Way to Honor the Old

Maybe your parents still insist on throwing salt over their shoulder. Maybe you do, too. The point isn’t whether these things are “true”—it’s that they’re part of a shared language we carry.

If nothing else, superstitions offer a starting point for bigger conversations: about culture, identity, memory, and change. And as Asian Americans, we’re in a unique position to translate the past into something that still holds meaning, even in a different world.

Final Thoughts

Superstitions aren’t just rules—they’re stories. And in Asian American households, they’re some of the few stories that haven’t gotten lost in translation.

So the next time someone says, “Don’t open that umbrella indoors,” maybe instead of rolling your eyes… ask them why. You might learn more than you expect.

And hey, if it keeps the ghosts away, even better.